Mangroves are a natural barrier against marine depredation:Dr. Donald Macintosh

It was a fascination with scuttling mud-crabs (Scylla) with their vicious pincer-claws and their shells sporting anything from a deep mottled green to a dark brown that led him to mangroves, a love of which has persisted over the years.

Not being satisfied with just studying mangroves, Dr. Donald Macintosh has become a strong advocate, flying from country to country, to spread the message on their importance. Interestingly, the mud-crabs which riveted his attention as a youth and continue to do so, are known to crab-lovers as the ‘Sri Lankan jumbo crabs’, which are threatened by habitat loss and over-fishing. (See box please)

The most recent visit to Sri Lanka of 65-year-old Dr. Macintosh was in May, to make a presentation on ‘Mainstreaming biodiversity: Sustaining people and their livelihoods’ to commemorate the International Day for Biological Diversity, on the invitation of Biodiversity Sri Lanka.

The day after his presentation, it was an exclusive interview with the Sunday Times in the morning, before travelling deep-south to give his technical expertise on coastal development to two hotels in Weligama and Hambantota, after which it was back to base in Bangkok, Thailand, for he is Senior Advisor at ‘Mangroves For the Future’ (MFF) in the Asia Regional Office of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Before we focus on the importance of mangroves, we turn the spotlight on the ‘man amidst the mangroves’ who has been working in this wide field of mangrove ecosystem management and inextricably-linked coastal conservation and development including sustainable fisheries and aquaculture, for more than 35 years.

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, he smilingly points out that it “can’t get more Scottish than that” before he speaks briefly of his academic achievements. It was when he was taking a course in Tropical Biology at Aberdeen University that the “great diversity” of the subject dawned on him. Feeling the need to work in the tropics, he applied for a Commonwealth Scholarship, as there was a research link between the University of Aberdeen and the University of Malaya.

“Off I went to Malaysia as a 21-year-old, unsure about what I wanted to do,” he says, adding that he was able to secure one of four Commonwealth Scholarships offered.

The mangrove fascination gripped him when he was studying for his doctorate on the ‘Ecology of crabs living in mangroves’ at the University of Malaya. This was the 1970s, and there were only three people in the whole country who were interested in mangroves, laughs Dr. Macintosh, describing how the early interest in shrimp farming in mangroves began in Malaysia, which in turn led him to look at the ‘economic uses’ of mangroves. “Mangroves were arousing an interest among businessmen which was making governments also pay attention to them.”

Then back home to Scotland went Dr. Macintosh to Stirling University’s Institute of Aquaculture, taking a deep look at how mangrove aquaculture could be developed. “In Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, I was interested in developing the aquaculture potential such as shrimps, blood cockles and crabs in mangroves,” he says.

His personal life too had taken a different pathway as by this time he had married Sherry (“as in the wine,” he smiles) whom he met at the University of Malaya. Sherry who is from Malaysia is now retired after working as a Local Government Service Provision Officer in Scotland.

The stint at the Institute of Aquaculture, Stirling University, was followed by Dr. Macintosh donning the mantle of Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA) Professor in Environment and Development at the University of Aarhus in Denmark, where he was also Director of the Centre for Tropical Ecosystems Research. Even though he is retired from there now, he remains an Adjunct Professor at the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) near Bangkok.

He has also managed several large coastal development projects in Southeast Asia including as Senior Technical Advisor to ‘Support to the Marine Area Network’ in Vietnam, Consultant to the World Bank/DANIDA funded ‘Coastal Wetlands Protection and Development Project’ in the Mekong Delta; and Denmark’s Coordinator of a DANIDA-funded Integrated Coastal Zone Management Programme at AIT.

From 2007 to 2011, meanwhile, Dr. Macintosh was the Regional Coordinator of MFF, a post-tsunami response involving Sri Lanka, India, Maldives, Thailand, Indonesia and Seychelles, and more recently also Bangladesh, Pakistan, Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam.

Going back in time to the deadly devastation of the tsunami, he says that the catch phrase put out by Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery, Bill Clinton, was ‘To build back better’. This is apt – there was forward-thinking to put back something better to help the coastal communities along the Indian Ocean. MFF was launched in December 2006 by Bill Clinton in Phuket, Thailand, with the symbolic planting of mangroves, with funding from Scandinavia, Norway, Sweden and Denmark, with smaller amounts from Australia, Germany and United Nations Agencies.

“Now it is almost 10 years since the launch of MFF and there needs to be increasing private-sector support, for they need to stand up and be counted,” says Dr. Macintosh, reiterating that MFF should get localized, as ownership is important for sustainability. It should be a three-way joint effort – local businesses, local community and local government – while universities and media also play a vital role. Technical advice and other speciality advice may be secured from outside.

Thereafter, Dr. Macintosh launches into his favourite topic………mangroves which are not only effective in warding off the effects of a tsunami but are also an asset to have around in severe floods, typhoons or cyclones.

“The mangroves physically protect a coastline against wave surges created by storms, with tsunamis being an extreme version of it. The mangrove root system is dense and strong and acts as a physical barrier by absorbing the force of tidal-wave surges while the mangrove forest will also absorb wind energy up to a certain amount,” he says.

Dr. Macintosh speaks with evidence in hand that a 100-metre wide belt of mangroves will reduce the velocity of a storm wave by 90%. This has been measured, he says.

Making us take a closer look at mangroves, this expert points out that their dense root system binds the soil, reducing soil erosion. When sediments are washed by rivers to the coastal zone, a lot of it is trapped by this root system, so there is no destruction of corals by the sedimentation. The flow of fresh flood water from land to sea is also slowed by mangroves.

“Globally, we’ve fragmented the mangroves and now we have them in patches. Therefore, effectivity is diminished. There is an urgent need to recreate quite a significant belt,” says Dr. Macintosh, adding that mangroves are also valuable in supporting fisheries – shrimp, mud-crab and a large number of fish species. What we don’t think of is that mangroves also harbour many insects and birds, in an environment of rich biodiversity.

The protection of mangroves should be incentive-based and not regulated, he is quick to point out. Mangroves need protection and management in a way where communities benefit. This, in turn, becomes an incentive for the community to become the guardians of mangroves.

Protecting our mud crab

Biodiversity is the ‘natural capital’ that we need to protect and use wisely, underscores Dr. Don Macintosh, pointing out that habitat and biodiversity loss and pollution are the widespread consequences of human activities. These impact on human health, food security and livelihoods while climate change and extreme weather patterns are adding to the threats faced by all natural ecosystems.

Biodiversity is the ‘natural capital’ that we need to protect and use wisely, underscores Dr. Don Macintosh, pointing out that habitat and biodiversity loss and pollution are the widespread consequences of human activities. These impact on human health, food security and livelihoods while climate change and extreme weather patterns are adding to the threats faced by all natural ecosystems.

Dwelling on what the ‘ecosystem approach’ is, he says it is astrategy for integrated management of land, water and living resources that promotes conservation and sustainable use in an equitable way.

Picking out the coastlines and seas within tropical Asia which are among the most productive and biodiversity-rich in the world, Dr. Macintosh explains that coral reefs and sea-grass beds provide the primary production and habitat needs of countless marine animal species, while mangrove ecosystems support hundreds of animal and plant species from diverse origins (marine, intertidal and terrestrial).

“Conserving these valuable, but fragile ecosystems and the biodiversity they support is made very challenging by a number of factors. They include the high levels of exploitation of aquatic species by coastal fishing communities and commercial fisheries and development pressures to increasingly urbanise and industrialise Asia’s coastal zones.”

Without sustainable (ecosystem-based) management, there is over-exploitation of natural resources; unplanned and unregulated coastal development; weak institutional responsibilities and poor governance which lead to habitat degradation, erosion, pollution, aquatic diseases and loss of valuable species, fisheries and livelihoods, it is learnt.

Here, Dr. Macintosh delves deep into the mangroves and picks up the mud-crab citing the case study of the ‘Sri Lankan jumbo crab’. Moving among mangroves, inshore and offshore habitats during its life history, which includes phases as a planktonic, crawling, burrowing and swimming organism, this iconic and valuable crustacean is severely threatened by habitat loss and over-fishing.

The mud-crab is the most mangrove-dependent fisheries resource supporting local livelihoods, but is severely over-fished, according to him.

“Immensely important to the food and livelihood security of millions of coastal- and river-dwelling people globally and especially across Asia, the commercial species are part of complex food webs. However, they have been heavily impacted by over-fishing, habitat loss or degradation and pollution,” laments this expert.

This is why Dr. Macintosh is urging a “common vision” for healthy coastal ecosystems, to bring about a more prosperous and secure future for coastal communities.

Otherwise, for Sri Lankans a sumptuous, finger-licking good crab curry may also become just a dream.

Kelani River Conservation: The key to a bright future

By Yasara Kannangara and Ananda Mallawatantri

Water is one of nature’s greatest gifts to humankind. However, wide scale pollution has made it apparent that this precious gift is often overlooked and neglected, as is the case of the Kelani River and its basin.

The Kelani River Basin Multi-Stakeholder Partnership is a project developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) using the local inputs of more than 60 agencies and international literature, under the supervision of the Central Environment Authority (CEA) with UNICEF funding to alleviate the disturbing levels of pollution in the Kelani River Basin. The plan spanning from 2016 to 2020 aims for the sustainable development of the basin through a range of catchment protection and strategic shifting from industrial base to nature base income sources capitalising on the thriving eco-tourism industry.

Being true to the famous saying of French writer, historian and philosopher Voltaire “Is there anyone so wise as to learn by the experiences of others?” the multi-stakeholder also hopes to study and incorporate global experiences on river restoration to the project. Nevertheless in integrating these experiences the stakeholders also consider the social, economic, political and cultural relevance to the country.

Maintaining water quality is essential to achieve sustainability within the basin as it helps identify pollution types and potential sources. For example, high amount of sediments in water is an indication of agriculture or urban erosion issues whereas, the presence of high E.coli bacteria denotes poor sanitation facilities. This includes presence of sewage in the river.

The Thames-Sydenham Water Source Protection Programme is a project based in Ontario, Canada. It was established to counter similar issues and was aimed at decontaminating drinking water which was polluted due to improper sewage disposal. Through the project, definitive steps were taken to improve septic systems and other facilities. Similarly, it is imperative to build better facilities and sewage disposal methods in the Kelani River Basin as contamination of water with human waste is a pressing issue in the basin.

However, industrial pollution is the main cause that has led to the wide scale pollution in the area. Despite this, industries can be deemed as a necessary evil in today’s world. However, this does not mean that industries cannot exist side by side with nature. On the contrary, the Chesapeake Bay Programme in the United States has proved that industries and a pollution free environment can exist alongside one another. Despite the large number of industries in the area the bay remains to be one of the cleanest water bodies in the country. It is also home to a large scale seafood industry, especially in regard to crabs.

A venture such as this is at present impossible in the Kelani River as the water is contaminated with heavy metals which has had a

detrimental impact on the aquatic life forms in the river and will also adversely affect humans who consume them. However, the Chesapeake Bay lends the Kelani River hope that such a project to recreate a new image for the river is indeed possible. However, to achieve such a spectacle it is a must to ensure that all industries within the Kelani River adhere to the environment protection standards that are imposed by the CEA and the National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWSDB).

The present water quality standards based on the American Public Health Association (APHA) have contributed much towards the reduction of pollution in the river but they are not without drawbacks. As such, the industry-centric nature of the standards can be regarded as the main weakness. Hence, to truly eradicate the contamination of the river an expansion in coverage is necessary. For this the multi-stakeholder partnership has adopted United States Environment Protection Agency (USEPA) derived water quality guidelines and management approaches as much as possible.

River bank erosion due to illegal sand mining is also a major threat to the water quality of the river. To prevent this, the stakeholders have proposed to establish a sand mining monitoring police unit. The Ganga Action Plan (GAP) for Ganga River Basin in India is an instance where such actions have been successful. Under this project, a National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) was set up to plan, finance, monitor and co-ordinate the effective abatement of pollution and the conservation of the river.

Additionally, the limited amount of sampling sites for water quality is also a drawback in safeguarding the resilience of the basin. While there are 13 existing sampling locations they only cover part of the basin. This is not adequate to ensure water quality in the entire river. Therefore, new sampling sites should also be established. Automation is an option that is being considered to achieve these objectives with ease.

Although, the initial cost of water quality monitoring may seem excessive at a glance it can be regarded as a worthwhile investment. This is because monitoring the quality of water ensures water safety. Sri Lanka already spends an exorbitant amount of money on health issues such as kidney diseases linked with water pollution. If the situation remains unchanged the cost of health will only rise higher and higher. Hence, the amount to be spent can hardly be predicted or calculated. In such a circumstance, implementing measures to examine water quality can be seen as a long-term solution.

Implementing water quality standards is a challenging task. For this constant monitoring of water is indispensable. The KRMP approach intends to seek expand the present water monitoring by CEA, National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWSDB) and Irrigation Department with the help of the Sri Lanka Standards Institution (SLSI) and other institutions including universities.

Moreover, the Kelani River Basin can be described as a nature lover’s paradise even with the massive pollution as it lays claim to a myriad of scenic locations that are abundant in natural splendour. However, this reputation enjoyed by the basin is fast diminishing. Despite being a place of natural beauty the potential of the Kelani River Basin remains largely untapped. Indeed, the basin encompasses many attractions with the Kithulgala/Kelani Forest Reserve, Muturajawela wetlands, Negombo and Sithawaka Botanical Gardens being only few of the locations.

The river also contains international level rapids that are suitable for white water rafting. Yet, it is a far cry from being an ecotourism hotspot. The KRMP approach was partly influenced by the “Healthy Parks Healthy People” initiative in Australia and Bhutan’s concept of “Gross National Happiness”. They highlight that nature and happiness are entwined hopes to create an environment which is conducive to both physical and mental wellbeing through nature. By doing so the project envisions a future free of pollution and related diseases while ensuring the income base in the basin improved.

(Yasara Kannangara is a student in languages and Ananda Mallawatantri is the Country Representative of IUCN Sri Lanka)

Uma Oya Project Throws Up Fresh Challenges

Villagers in and around the ongoing Uma Oya Project say they are facing severe water shortages due to the tunnelling that led to a `water leak’ a few days back.

Naturalist Indaka Kamaladasa, a resident of the area, told The Sunday Leaderthat a number of brooks and wells have dried up within the last 10 days. He warns that the trend could worsen.

“We are experiencing a similar situation that occurred when the project was commenced in January 2014. We fear that if the right measures are not taken immediately, the situation will worsen,” he stressed.

When contacted, Oma Oya Project Director Dr. Sunil de Silva said they were aware of such problems but considering the socio-environmental issues, they were cautious in carrying out their task. He added that they were taking all possible measures to minimise the impact.

He said that usually between July and August, wells dry up because of the hot weather conditions.

Tunnelling in Uma Oya continues despite more wells turning dry in the Heel Oya area in Bandarawela. The report submitted to the Supreme Court shows that original ingress of water (450 L/s) was reduced to 60/70 L/s before sealing and after sealing it reduced to 47 L/s. However, when the drilling operation continued, it has increased to 110 to 125 L/s. This proves that they are tunnelling through the shallow water aquifer, says Hemantha Withanage, the Executive Director, the Centre for Environmental Justice and Director Friends of Earth (FoE), Sri Lanka

“It is evident that since restarting the tunnelling in January 2016, more than 20 wells along the tunnel have dried up. This is a serious ecosystem damage that should be immediately stopped and the tunnel needs to be redesigned. If not this mountain ecosystem will be seriously damaged. This is clear ignorance of the monitoring bodies including the Central Environment Authority (CEA), Withanage added.

The Uma Oya tunnel is being constructed to bring Uma Oya water to ‘Ali Kota Ara’ in the Kirindi Oya river basin. It was designed to drill about 300 meters underground to have approximately 600 m head to generate maximum electricity, he said.

The tunnel collapsed in the Heel Oya area in December 2014 and more than 2500 houses got damaged, while 17 of these are not conducive for living in anymore.

“Hundreds of drinking water wells dried up in a few hours. Since then people were provided with a limited amount of water. No compensation has been paid so far,” Withanage added.

He noted that the ecosystem damage is far more serious than the damage to the people. The tunnelling has resulted in breaking the limestone soil structure. It has damaged the water aquifers in the area. Even if the tunnel is completely sealed, it will not repair this soil structure.

He also pointed out that some officers assure people that the water table will be regenerated. Even if the sealing is done, it does not ensure that the water table can be regenerated, as there may be many internal changes of the aquifer. The new document claims that sealing has fixed things where the confining layer was pierced. However, that may not last long if any cracks develop in the material.

The majority in the affected areas are farmers. Even the others who are engaged in employments used to cultivate vegetables to earn an extra income and to consume, he says.

Drying up of water springs, streams and other natural water sources resulted in the farmers having difficulties in cultivating in the last four seasons from December 26, 2014. It is unfortunate that the government turns a blind eye to the issue which is a life and death situation for the villagers.

CEA officials said that the project contractors had not properly followed the conditions in the final EIA approval.

“They have not followed environmental standards that the EIA mentions,” they said, adding that the project contractors had violated a main condition of drilling and blasting in the presence of the officials from the Geological Survey and Mines Bureau (GSMB).

Referring to the earlier problems and the repetition, they said that this unexpected disaster – cracking of houses, and wells and springs running dry – occurred as they had not followed the conditions given in the EIA.

Project Director Dr. De Silva said that the initial study was carried out by Lahmeyer International from Germany in 1987 and another study was done by a German consultancy firm in 1989.

Dr. De Silva said that after the final report was submitted, the public was given time to lodge their comments. “The CEA received over 110 public comments from many environment, farmer community organisations and villagers. The CEA studied all those and approved the EIA in 2011. Accordingly, three years was given to the project to get proceed. The members of the CEA’s monitoring committee visited the project site and gave another three years till 2017 and recommended to implement some conditions in July 2014,” he said.

Construction apart from essential works required to prevent the risk by sealing the water ingress in the head race tunnel, have been temporally suspended since February 16 until a decision is made according to the recommendations of the Central Environmental Authority and the Special Intellectual Committee appointed in this regard. The respective reports have now been issued and many measures have been recommended to rectify the problems. Many of the recommendations are to be carried out by the contractor, and the government plans to arrange a post-inspection mechanism to prevent such situations in the future. President Maithripala Sirisena, who is also the Minister of Mahaweli Development and Environment, recently visited the people affected by the project and assured them that the government will address their grievances. He instructed officials to immediately provide a report on the progress of the project, financial situation, and relevant public views. The multi-purpose project involves the construction of two reservoirs on tributaries of the Uma Oya, which flow from the central hills and join the Mahaweli River, and one tunnel of the Uma Oya to divert water to a power generator further downstream.

The water will be diverted to Kirindi Oya basin which will take water to Hambantota through the 25 km long underground tunnel across mountains in Bandarawela by constructing a dam at Puhulpola in Welimada and a reservoir in Diaraba. The proposal that President Sirisena made to rebuild about 600 destructed houses and to continuously provide drinking water for the affected families by the National Water Supply and Drainage Board has received approval from the Cabinet.

Secretary of the Environment and Mahaweli Development Ministry Nihal Rupasinghe said priority had been given to repair the tunnel leakage since it was causing significant damage to water resources. He said there were no immediate plans to relocate villagers, but Rs. 25 million had been released along with instructions to the AG to compensate for the damaged houses.

“We will consider relocation as well,” he said and added that the project authorities had been asked to rectify the damages before they proceed with the project.

“We are waiting for a comprehensive report from the expert panel. Once we received it, we would submit it to the Cabinet sub-committee,” Rupasinghe said.

The report will be prepared by the experts of the CEA, National Building Research Organisation, and GSMB. A team from the University of Peradeniya will also support in this regard.

Sajeewa Chamikara of the Environment Conservation Trust has also urged the government to stop the project since it would cause a huge disaster. He said that the main cause of the present situation is due to the construction of tunnels to carry water from Puhul Oya reservoir to Dyraaba reservoir.

“They have completed 16 per cent of the tunnel. When the 26 km-long tunnel is completed, the hilly areas of the Uva Province will be prone to severe landslides as constructions is carried out,” he warned.

“Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa and the CEA should be held responsible for putting people in danger by implementing this failed project,” Chamikara stressed.

Civil organisations, environmentalists and people in Bandarawela staged several protests demanding to close the project and urged the government to protect them. They have now decided to continue with their protests until the government take a stern decision on the issue.

Last year, the Central Engineering Consultancy Bureau (CECB) and the Department of Valuation were asked to carry out an assessment of damage in order to compensate for properties including 1,500 houses affected by the Uma Oya project. Accordingly, they have recommended a payment of Rs. 200 million to be made.

Two roller compact concrete dams, an underground 134-MW capacity hydropower plant, and 25-Km underground tunnel.

Once completed, the project would irrigate 5,000 hectares of agricultural land.

The project is estimated to cost USD 529 million. The government will meet 15 per cent of the cost while the Export Development Bank of Iran will grant USD 450 as a loan.

During a visit of the former Iranian President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, in 2008, an agreement was signed to provide financial and technical assistance to Uma Oya project.

“The contractors have done a lot of damage by not adhering to the environment plan,” Rupasinghe said. He, however, stressed that the project is feasible.

“There is nothing wrong with the project. Similar issues cropped up when other hydro projects like the Victoria Dam was under construction,” he said.

The contractor, FARAB Energy and Water Project Company, an Iranian company, is responsible for carrying out the project.

President Sirisena appointed a five-member Cabinet sub-committee last year to make recommendations. Rs. 300 million has also been allocated to provide reliefs to the affected people. The sub-committee was comprised of Finance Minister Ravi Karunanayake, Power and Energy Minister Champika Ranawaka, Internal Transport Minister Ranjith Madduma Bandara, State Minister of Housing and Samurdhi Dilan Perera, and Minister Harin Fernando

A cry from the wilds of Mannar

Save this area’s unique eco-systems and the animals that inhabit them from short-sighted development plans, pleads environmental activist Dr. Sampath Seneviratne

Tread very carefully when leaving a development footprint on this island, for it could do more irreparable and irrevocable harm than good, urge environmentalists.

While in some parts of Mannar Island which covers about 195sqkm any development or human intrusion could crush hundreds of bird-eggs scattered on the ground, in other parts it could be a danger to the mammals, such as spotted deer, feral horses and donkeys which roam the area.

The stark image on the need to free Mannar Island from human encroachment is a beautiful spotted deer, taking a leap from one side of what used to be its home to the other side. Now, its wilderness is under threat, divided by a five-foot high barbed-wire fence. What awaits the deer on the other side is not freedom but more danger in the shape of nasty nooses and cruel traps put in place by man.

The onslaughts on Mannar Island are coming in different forms such as deforestation, illegal encroachments, land-grabs and constructions with allegations that massive projects such as the installation of wind turbines would also toll the death knell for this biodiversity-rich beauty-spot, environmentalists lament.

It is a very emotional environmental activist, Dr. Sampath Seneviratne, Research Scientist on Molecular Ecology & Evolution and Senior Lecturer in Zoology, Colombo University, who has trudged every inch of the island and knows it like the back of his hand, who pleads for intervention both by the authorities and the public.

“Their (the deer and all creatures on Mannar Island) land has been robbed from them. They desperately need help…. help from all nature lovers. The last of this sensitive and unique habitat (the sand dunes of Mannar Island) is fenced – ready to be destroyed forever. Is there a way to safeguard the remaining few patches of it and all its beauty,” he asks, blaming humanity’s greed, insensitivity and injustice towards these creatures.

“The effects of such unplanned activities will be extremely harmful for the long-term survival of Mannar Island,” reiterates Dr. Seneviratne.

Numerous appeals to the District Secretariat officials seem to have fallen on deaf ears, even though the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) has been quick to respond to urgent pleas whenever specific instances of destruction have been pointed out to them, it is learnt.

Dr. Seneviratne highlights each and every aspect of what is unique about Mannar Island. According to him it has four exclusive eco-systems, not found anywhere else in the country.

Vankalai mudflats – In ultra-low tide, they take on a desert-look, metamorphosing into a lagoon at ultra-high tide. Around 100 species of birds with different beak types access different layers of the water and silt-like mud which is replete with invertebrates such as molluscs and annelids while the ‘forest’ under the mud harbours tasty morsels such as crabs and lobsters for other birds. This unique system supports millions of birds, both migratory and resident, which feed and breed in this undisturbed habitat.

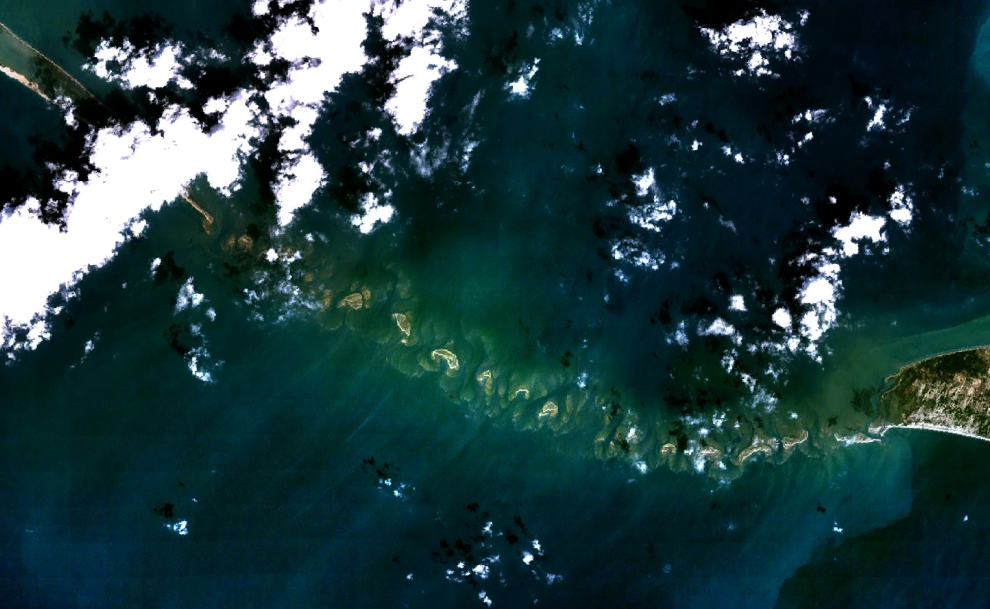

Adam’s Bridge sand dunes and sandy islands – This habitat across 13km with no trees except for a few shrubs provides the ideal environment for animals which hop or fly. The hopping creatures cross when the sand-bars show up during ultra-low tide. This area also serves as a mixing and transferring bowl for Sri Lankan and Indian genes among fauna and flora. With land predators such as dogs, cats, mongooses or snakes unable to cross the waters to the 3rd and 4th islands forming Adams’s Bridge, 11 endangered species of birds lay their eggs, sans nests or any kind of protection, on the bare earth here.

n Sand dunes on the main Mannar Island – These are some of the most well preserved natural sand dunes in the whole of Sri Lanka, where the spotted deer roam, the jungle and fishing cats slink about, wild pigs snort around, the Dry Zone slender loris can be sighted, while a large number of birds can also be seen. This unique desert system bearing similarities to north Sri Lanka and southern India, is used as ‘a staging and re-fuelling area’ by the smaller migrant birds flying from the Himalayan foothills.

Korakulum wetland – This wetland with fresh water on Mannar Island attracts not only fishing cats, feral horses and donkeys, but also numerous bird species, including the breathtaking flocks of Flamingos.

Pointing out that the whole of Mannar Island has a “huge” significance in the global migratory pathways of a large number of birds, Dr. Seneviratne singles out Korakulum to push home the message for the need to protect and safeguard the area. He describes how Korakulum reflects the rainy and dry seasons, with the wetland water body being ringed by scrub forest. At the height of the dry season, the area becomes a grass-land.

“The mudflats within this wetland are an excellent feeding ground for shorebirds and other aquatic birds during the winter months. When the mudflats dry up during the summer months, they turn into breeding grounds for eight species of birds, two of which are listed as ‘threatened’ species in Sri Lanka’s National Red List,” he says. “It is one of the major wetlands in the Mannar area – the only freshwater lake available for both migratory and resident birds.”

Picturesque are the images, this bird specialist creates in the mind’s eye, substantiated by stunning photographs, for he himself has seen 62 species of land birds, 13 species of seabirds, 26 species of shorebirds and seven species of diurnal raptors from October to April during his walkabouts on the island.

It is also an important breeding ground for resident birds such as the ‘critically endangered’ Spot-billed Duck (Anas poecilorhyncha); ‘endangered’ Large-crested Tern (Sterna bergii), Roseate Tern (Sterna dougallii), Common Tern (Sterna hirundo and Long-tailed Strike (Lanius schach); and ‘vulnerable’ species such as Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrines) and Little Tern (Sterna albifrons), the Sunday Times learns.

Korakulam is also a critical feeding ground for more than 10,000 migratory birds including gulls, ducks, storks and shorebirds, says Dr. Seneviratne, adding that the ‘globally vulnerable’ Great Knot (Calidris tenuirostris) uses this wetland annually. Several locally important species such as the Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus), the Great Black-headed Gull (Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus), Heuglin’s Gull (Larus heuglini), Eurasian Spoonbill (Platalea leucorodia) and Northern Teal (Anus crecca) are also frequently spotted here.

Not only is it a paradise for birds, according to this naturalist, for the feral horse (Equus ferus) and donkey (Equus africanus) graze in this wetland, while the Jungle Cat (Felis chaus) and Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) as well as endangered butterflies such as the Large Salmon Arab (Colotis fausta), Crimson Tip (Colotis danae) and Joker (Byblia ilithyia) are also found here.

It is in utter despair that he speaks of the mounting threats which include illegal encroachment with land-grabs and scrub-forest clearance being carried out with impunity. Giving specific examples, he says that the land around the lake has been partitioned into a large number of 10-perch lots as well as big lots of about an acre or more by fence posts and barbed-wire fencing. Some of these fences cut right across the wetland.

The scrub forest has also been cleared, laments Dr. Seneviratne, pointing out that even the historic Baobab trees have been uprooted and burnt in adjacent areas. Aggravating the situation, two gravel roads have been constructed as access roads to some of these cleared lands.

Garbage and refuse are being dumped on the northeastern boundary of the wetland near the dam, with the high winds littering the wetland with muck.

Meanwhile, the illegal trapping and shooting of waterfowl in Korakulam goes unabated and from the descriptions Dr. Seneviratne has garnered from the culprits he identifies the victims as migratory species such as Pintail and Gargany Ducks, and large gulls such as Great Black-headed and Huglin’s Gulls and also Grey Partridge, with sadly even the endangered Spot-billed Duck may be going into the cooking pot.

The need to conserve mannar island is apparent. It should be done not tomorrow or the next day but right now.ewha