700 to 1,000 leopards in Sri Lanka; researcher

There are about 1,000 leopards across Sri Lanka and they are a keystone species in ecological parlance of the country, a wildlife researcher has said.

An article published on the website of multimedia publication ‘Motherboard’ under the title ‘Saving Leopards Is Hard, Especially with All the Landmines’ by Smriti Daniel, said leopards are more important to the ecosystem than their numbers would suggest.

Wildlife researcher Anjali Watson has said that leopards are an “umbrella species” – because they are wide-ranging animals, protecting them would mean protecting many others in the same territories.

Wilpattu, Sri Lanka’s oldest and largest national park, was once a warzone. The fighting between the Sri Lankan state and the militant separatist group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) that began in the 1980s had spilled over into these wild lands.

Wildlife researchers Anjali Watson and Andrew Kittle remember hearing stories from soldiers stationed in these forests. The men recalled nights when they would be jolted awake by the sound of landmines exploding in the pitch darkness, somewhere beyond the border of their camps. Nervously, they wondered whether guerillas had triggered the bombs, and if their enemies would soon close in on them.

But the dawn would bring evidence of a different kind of victim. The remains of peacocks were found lying in heaps of shredded feathers; elephants lay with limbs blown off. “A few leopards and bears were also shot because men who encountered them were afraid,” Watson told me, explaining that the thick, thorny forests often swallowed any evidence.

The park itself was off limits to the researchers during the conflict. But even after a ceasefire signed in 2002, it remained unsafe—a mine claimed the lives of a jeep full of wildlife enthusiasts in 2006 and a year later, Wilpattu’s park warden Wasantha Pushpananda was ambushed and killed by the LTTE while on an inspection tour with his team.

It wasn’t until the nearly 30-year-long war came to an end in 2009, and many landmines laboriously cleared, that Watson and Kittle were able to readily move about Wilpattu again. They are now publishing data from one of the most comprehensive studies of the leopard population in Wilpattu—the first since the Smithsonian Institution did a more general survey in the late 1960s.

A husband and wife team, Kittle and Watson head The Leopard Project at the Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust (WWCT) in Sri Lanka. They have been studying leopards for over a decade and were responsible for gathering the data that put the native big cat on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of endangered species in 2008.

“Being on the Red List influences both conservation and funding attention,” Watson said, explaining that IUCN tracks the global status of various species. In Sri Lanka, the state’s conservation programs had previously been focused overwhelmingly on the elephant, but the IUCN listing has driven a surge of interest in the leopard and its significance as an apex predator—residing comfortably at the very top of the food chain on this island.

Kittle, Watson and I meet in their small office, perched above a garage in central Colombo, the commercial capital of Sri Lanka. The two sit across from each other and share a desk, seeming to be seldom out of each other’s company. Their rhythm has roots—the two met in university and have since travelled widely, always working closely together as a team. When their children were born, they simply took the kids along to the field, something they continue to do. Little drawings by Ayla and Amara decorate an entire wall in their office.

Watson said she and Kittle first knew they could make such a close partnership work when they were assigned to help reestablish a wild population of native primate species on an uninhabited island on the Panama Canal in the late 90s.

“There was just the two of us, and a guard who spoke Spanish,” Watson tells me, laughing. “I spoke no Spanish, Andrew spoke some Spanish, and the only other contact we had was a boat coming in every Saturday to bring us provisions. We spent nearly two years there, and I thought if we could do this…”

Today, though their work still might take them far afield, Sri Lanka is home—Watson said her heart is with this island because she grew up here. The duo are working toward establishing a comprehensive habitat use plan for the Sri Lankan leopard by 2020, including a population distribution map, and assessments of its habitats across the island. But tracking this predator has always presented a challenge.

When Watson and Kittle first told me this, I was surprised. I have seen leopards in Yala National Park in southeast Sri Lanka, where the big cats draped themselves decoratively over high branches and rolled around on dusty trails as tourists watched. But Kittle explains that in Wilpattu, and pretty much everywhere else in the island nation,the Panthera pardus kotiya is notoriously shy.

“Usually cryptic carnivores like this are really difficult to spot,” he said, adding that leopards manage to remain elusive despite existing in relatively high numbers in little pockets across the island.

Now, in the Peak Wilderness Sanctuary in central Sri Lanka, where tea plantations abut dense forest, encounters between leopards and people are on the rise. As more and more wilderness is cleared, Kittle and Watson say leopards and other animals are increasingly moving around and even breeding in ‘habitat mosaics’, or heavily fragmented forested areas surrounded by a patchwork of farms, plantations and homesteads. As a result, villagers are reporting more leopards sightings.

With one legendary exception—in the 1920s, the ‘maneater of Punanai’ was a voracious killer—Sri Lankan leopards are not maneaters.

In Dickoya, people have escaped encounters with the animal with just some deep scratches. Watson and Kittle, increasingly called on to reassure nervous communities, use these incidents to help convince villagers that the leopards are likely as frightened of the people as the people are of them. Working closely with the management of sprawling tea estates, they are now trying to find ways to prevent humans from barging in on the leopards. But to do this, they first have to know where they will be.

In the years that Watson and Kittle have been out in the field, they’ve seen the tracking technology available evolve. In their earliest forays into the field, they would rely on sighting the animals directly and recording each encounter. Some of Yala’s leopards, such as one who boasted bold spots in the shape of a ‘W’ on his forehead, were immediately recognizable, others could only be identified by closely examining photographs of the unique pattern of rosettes on their bodies.

The couple would also rely on tracing Paw Impression Pads: sweeping leaf litter away from a likely spot, they would create a sandy clearing, then return to record pugmarks. This technique allowed them to set up TrailMasters, camera traps that ran on film, to monitor spots where there was a lot of leopard traffic.

Watson and Kittle stuck with the technology up until 2012, before they switched to digital cameras. Film cameras could be cumbersome in the field, demanding hooking up wires and multiple components, but digital ones offered better battery life, were usually more weather resistant, and enabled them to get results faster and cover larger areas.

Ironically, conservationists must often rely on technology developed for hunters, Kittle said, but at least there are hundreds of cameras to choose from. Currently, they use Scoutguard SG565F cameras which have an incandescent flash (old style, bright white). “This is not de rigueur these days in remote camera work as infra-red or low-light flash is the thing,” Kittle said.“But we need to identify individuals in order to estimate population densities etc. and only incandescent flash is capable of that for a moving animal.”

However, the technology still comes with its own share of glitches. “The camera trap is triggered by data from a highly sensitive Passive Infra-Red motion sensor,” said Watson, adding that deploying this technology in Sri Lankan parks has been a steep learning curve. “In Wilpattu we found that the sun rays in the morning could interfere with the beam, and we would have 3000 shots of sunlight,” she said.

“In the Horton Plains dew and mist would trigger the trap, in Ritigala ants were building nests inside the lens, and in the Peak Wilderness Sanctuary we have all these pictures of leopards with a spider web across one corner of the image. Thank god, they were still usable.

” Watson says that there are between 700 and 1000 of this apex predator across the 65,000 sq km island. “They are a keystone species, in ecological parlance,” Watson told me,“They are more important to the system than their numbers would suggest.” She explained that leopards are an “umbrella species” – because they are wide ranging animals, protecting them would mean protecting many others in the same territories.

The team uses scat—i.e. leopard feces—analysis to understand the leopards’ diet and hunting patterns. “Felids have very short guts and pass out hair, bones, nails, quills etc. undigested,” said Kittle. Efforts are underway to fine tune mathematical equations that can then transform scat analysis output into an estimate of biomass consumed, providing a clearer, more reliable picture of leopards’ dietary choices.

Kittle and Watson have watched the post-war transition with interest, and have been curious about the conflict’s impact on local wildlife. Watson points out that war can lead to decimation of habitats and rampant poaching, but that in other cases “mines can also keep people out”, somewhat protecting wildlife from human intervention or development.

Now, as people return to the formerly war torn areas in the north and east, they have begun reclaiming lands or clearing new acres in previously untouched areas like the sprawling forests of the Wanni. They’re building homes and preparing the once wild land for farming. But this trend is not confined to one part of the island, and everywhere protected areas are coming under threat.

“I think the big concern is the pace of this whole post-war development drive,” warns Watson. “There is so much we don’t know, so many areas we haven’t explored. We could be losing species we never even knew about.

But Kittle said studying the leopard has left him “tentatively optimistic.” “For us, there’s always this thrill, no matter how often you see the animal. You have this respect for its ability to exist in very compromised locations, often alongside people, with minimum conflict. You have to admire that.” –

http://www.dailymirror.lk/article/-to-leopards-in-Sri-Lanka-researcher-121683.html#sthash.sRtrpbKf.dpuf

Fire Erupted in Alugolla Forest Reserve in Badulla

A fire has erupted in Alugolla Forest Reserve in Badulla yesterday successfully been extinguished.Badulla police, Army, villagers and the Fire Brigade of the Badulla Municipal Council had put the fire out together.

An estimate of 30 acres of land was destroyed by the fire. Police suspects that animal hunters may have put up the fire in the reserve.

Source – 02/05/2017,Fast News, see more at – http://english.fastnews.lk/44252

Gentle marine giant drawn to our waters

View(s):

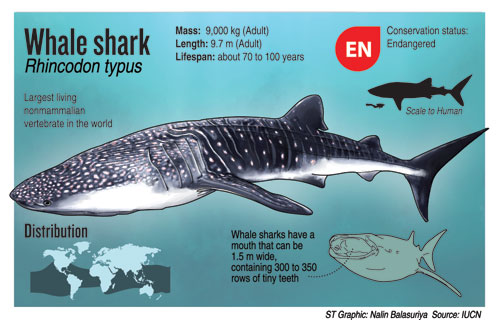

As the sightings of whale sharks increase in our waters, experts say the world’s largest fish needs to be protected.

“We still know very little about whale sharks, but the fish is already ‘endangered’ and highly threatened by both target and bycatch fisheries,” says marine biologist from Blue Resources Trust, Daniel Fernando. He made the remarks at a lecture at an event organised by Sri Lanka Sub-Aqua Club this week.

The blue whale is the largest creature on Earth, but since it is a marine mammal, the crown of being the largest fish goes to the whale shark. A whale shark can grow up to 40 feet (12 meters) or more and weigh about 20 tons. The average whale shark is 8 metres long, but the ones found in Sri Lankan waters are 6-7 metres according to Mr Fernando.

Scientifically classified as rhincodon typus, the whale shark called ‘mini muthu mora’ in Sinhala is in fact a species of shark. But unlike other sharks, they do not have teeth and they are filter feeders that depend on plankton. By opening their huge gaping mouths closer to the surface, they scoop in these plants along with any small fish.

Divers have reported more sightings in the seas off Colombo.

Nishan Perera, a marine biologist who has made regular dives in the oceans off Colombo, reported more whale shark sightings in February and March when these fish are seen in our waters. “Two or three whale shark sightings during this period is normal, but this year there were dozens of encounters,” Mr Perera said.

The Maldives is a famous destination for whale sharks and queries revealed a lower number of encounters in Maldivian waters when there was an increase in our waters said Mr Perera. The whale sharks have spots on the body and its pattern is unique for each individual. So, the Sri Lankan marine biologists also shared the photos of the whale sharks seen in Sri Lankan waters with other international whale shark databases to verify where they are from.

It could be the same individuals seen in different occasions, but the fact that they are seen more often means that the fish that are used to passing through our waters are staying a little longer than previous years.

Author of the “Sharks of Sri Lanka”; Rex I De Silva says the large number of recent sightings baffle him. He says these fish usually migrate to areas rich in plankton. These areas are where there is an upwelling of nutrient-rich water from the depths. So, it is possible that, fuelled by changes in hydrologic factors, such upwellings are now occurring with greater frequency in our coastal waters. Upwellings encourage the growth of plankton which, in turn, attracts other plankton feeders such as fish. Whale sharks also feed on fish (especially small scombrids) which are attracted to the plankton.

Changing oceanic patterns due to global warming is another reason according to the expert. However, these are just suggestions as to why whale shark sightings have become common in recent years. We just do not have sufficient data to draw firm conclusions, cautioned Mr De Silva.

Howard Martenstyn, another expert, points out that there are more nutrients in the western seaboard compared to 2016 as evidenced by increased rainfall and river outflows and that may explain more whale shark sightings. Mr Matenstyn also reminds us that the number of sightings in the same area does not usually equate to the number of whale sharks, highlighting the need for more supporting data and investigations.

The whale shark is a gentle giant, which allows divers swim with them. They pose no danger to humans but an accidental blow from the powerful tail can cause injury. Experts advise keeping a minimum distance of 1.5 metres from the front of the body and 3 metres from the rear.

The whale shark takes about 15 years to mature to reproduce and is vulnerable to overfishing. Sri Lanka passed laws banning the catching of whale sharks in 2015, but awareness of such regulations, along with implementation, is often lacking points out Daniel Fernando.

Source – 30/04/2017, The Sunday Times , See more at – http://www.sundaytimes.lk/170430/news/gentle-marine-giant-drawn-to-our-waters-238733.html

Animal architects

Dr. Sriyanie Miththapala looks at some of the amazing structures created by animal builders

The Burj Khalifa in Dubai is the world’s tallest building, with 160 storeys and towering at 829.8 metres. The Manta Resort on Pemba Island has underwater rooms where guests can watch sharks and rays floating past their beds. The Haohan Qiao Bridge in China is a glass-bottom bridge that is 179.8 metres tall and nearly 300 metres long. The pyramids of Egypt, the Colosseum of Rome, Borobudur in Indonesia and the iconic Taj Mahal of Agra stand as testaments to spectacular architects of the past.

Architecture is not new. Humans have been building since the Neolithic or New Stone Age from some 9000 BC to 5000 BC years ago.

However, animal builders have been in existence a long, long time before this — they are our planet’s first builders and they craft homes of mind-boggling designs.

Animals construct structures to a) build homes to raise their young and protect themselves against the elements or predators; b) catch or trap prey; and c) attract the opposite sex.

Colonial insects — termites, bees, wasps and ants — are champion architects. Individually tiny and vulnerable to being squashed, collectively, in a colony of millions, insects such as termites can build termite mounds that can be higher than five metres. It is estimated that the collective weight of these million termites is 15 kilogrammes, and that they can move a quarter of a metric ton of soil every year when they build these mounds using a combination of soil, saliva and excreta.

The mounds are marvels of architecture, with a complicated and extensive system of tunnels that generates ventilation and cools the air inside.This cooling is critical for these insects whose bodies would dry out in the arid environments of Africa, Australia and South America where they live. However, recent studies have shown that this complex system of tunnels does not merely generate passive air conditioning, but even functions like a giant lung to expel accumulated carbon dioxide and to pull in oxygen.

Prairie dogs — small communal mammals of the rodent family, found in the prairies of North America — go one step further, and build their own underground towns extending over some 40-50 hectares (that is, the size of 40-50 sports fields), with a maze of tunnels, defined sleeping quarters, nurseries, toilets and listening posts for predators situated close to the surface. These towns also have a built-in drainage system in case of flooding. They allow prairie dogs to raise their young in safety from predators and avoid the vagaries of the prairie weather, which can get too hot during the days in the summer and too cold at night during the winter.

Sociable weavers use different materials for different sections of the nest: large twigs and stems for the roof of the nest and grasses poked in between; grass spikes fencing tunnel entrances to deter predators; while nesting chambers are lined with soft materials, such as feathers, fluff, wool, or hair.

The advantage of this mammoth nest is again for protection against the elements and predators. During the day, the thatched roof of the nest keeps it cool from the scorching sun, and in the night, when the temperature drops sharply, the heat retained in the nest, keeps the colony of birds warm.

The north American beaver — another rodent — is second only to humans in its capacity to alter its environment, and is a master engineer, who gnaws through and fells trees across rivers, and then builds dams using boulders like bricks and mud like cement for construction, creating not merely a city or an apartment but an entire ecosystem — a wetland— safe from predators. Within this wetland, it constructs its home — called a lodge – a fortress of boulders and branches, so strong that a bear cannot break in. Beavers dig burrows underground into the wood around where they feed on plant material and then retreat to the safety of their wetland. These ecosystem engineers alter the flow of rivers, prevent erosion and raise the water table, purifying water as silt builds up and adsorbs toxins. All these changes attract a range of other species, such as invertebrates, amphibians, fish and birds.

Just as prey evolve mechanisms to avoid predators, predators go to great lengths to catch prey. Spiders produce silk protein from structures called spinnerets in their stomachs and weave webs to trap their prey. Trapdoor spiders do not weave webs like other spiders, but live in burrows which they did underground. They construct doors for these burrows using silk from their bodies, plant material found in the environment and soil. They then ingeniously make a hinge for these doors with silk and booby trap the surrounds also with their silk, close the perfectly camouflaged door, and wait underneath it. When an unsuspecting animal trips the booby trap, the spider springs out and kills it.

Animal architects also build to attract mates. The drab bower birds of Australia and New Guinea are extraordinary builders and decorators, where the male builds a bower for his mate and decorates it with various objects such as berries, flowers, shells, drinking straws, keychains and bits of plastic. The female chooses the best decorated and neatest nest. Among these astonishing builders, is the Shan Jahan of bower birds, the Vogelkop bower bird who builds a cone-shaped metre-high bower, woven around a central sapling, which he then carpets with moss. He carefully decorates the entrance with flowers, berries and coloured stones, all arranged according to an intricate pattern of colours. This process takes nearly a year, during which the male assiduously cleans and rearranges the area. Each bower is different as each male prefers a different set of colours.

In a world where we have over-used natural resources, destroyed natural habitats and poisoned the air and water to alter the environment to suit us, it may benefit us well to turn to nature and learn from it.

We may now be striving for sustainability, but a sustainable world already exists in nature which has fine-tuned its products during a 3.8 billion year period. Termite mounds have a sophisticated air-conditioning system that uses no fossil fuels to keep the structure at a temperature that fluctuates only within one degree Celsius, while we humans use 20% of the world’s energy to keep buildings in cities at similar temperatures. Corals are tiny colonial marine animals that extract calcium carbonate from the sea and secrete it as a cup of calcium carbonate from the bottom half of their bodies, building great ramparts of coral reefs. In doing so they lock in this carbon. In contrast, when we use cement to build infrastructure, approximately 900 kilogrammes of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere when each tonne of cement is made, contributing to global warming, We extract natural resources, turn them into short-lived products and after using them, we chuck them out as waste. Nature, on the other hand, never throws anything away — what is waste for one organism becomes food for another and is eventually recycled as nutrients into the ecosystem.

As Janine Benyus writes, ‘Nature runs on sunlight. Nature uses only the energy it needs. Nature fits forms to function. Nature recycles everything. Nature rewards cooperation. Nature banks on diversity. Nature demands local expertise. Nature curbs excesses within. Nature taps the power of limits.’

Benyus coined the word biomimicry to popularise this concept of looking to nature to provide sustainable solutions. In the last three decades, this branch of science has grown and developed producing some inventive solutions to our planet’s problems.

Inspired by the self-sustaining air-conditioning systems of termite mounds, Zimbabwean architect Mike Pence designed the Eastgate Building, an office complex in Harare. Made mainly of concrete, this building has a ventilation system which draws outside air using fans into the building and this air is warmed or cooled by the building depending on which is hotter, the building concrete or the air. This air is then circulated through the building before it is sent out, again by fans through chimneys at the top. This building uses 90% less than the energy of a conventional building its size and its owners have saved 3.5 million USD by not installing an air-conditioning system, excluding the cost of running it daily.

Matthew Parks of Atlas Industries looked at the Fogstand beetle of the Namibian Desert which lives in a harsh, arid climate where water is scarce. In the nights, when fog collects in the air, this beetle raises its back into the air. Parts of its shell-like external skeleton is waxy and repels water, while other part of it has bumps that collect the water as droplets, which then runs down along chutes towards the beetle’s mouth. Park designed the Namibian Hydrological Centre of Excellence, called the ‘Fogcatcher’ with ‘sails’ to catch water from the desert fog, to meet the growing challenge of finding drinking water in a desert area. Pak Kitae of the Seoul National University of Technology, had a simpler solution, making a Dew Bank Bottle that similarly collects morning dew on a bottle.

One of the most elegant biomimicry innovations is the Cardboard to Caviar project, that imitates the closed loop of an ecosystem’s recycling processes. Graham Wiles, the CEO of the non-profit Green Business Network (GBN) in Yorkshire, commenced this project as work rehabilitation for recovering heroin addicts. Restaurants pay the GBN to take cardboard from their premises. GBN does so, shreds it and sells it as horse bedding. Eventually, the bedding needs replacement, and the stable owners pay GBN to replace it. GBN takes the soiled bedding and feeds it to worms to make compost. The compost nourishes plant beds and the extra worms are fed to the sturgeon in a fish farm. Caviar is produced from these fish, and sold back to the restaurants where the cardboard was collected in the first place. This is an excellent example of how every link in an ecosystem reuses waste and recycles nutrients. That it takes the pressure off the endangered wild sturgeon, is an added bonus.

These are exciting innovations that can change the way we think and, the way we can live sustainably, in harmony with the Earth. In order to do so, we must stop ravishing the earth of its bounty and learn to look and listen to the lessons it gives us freely.

Source – 30/04/2017, The Sunday Times, See more at – http://www.sundaytimes.lk/170430/plus/animal-architects-238352.html

Bopitiya dump stirs up garbage danger, anger

In its haste to dump garbage anywhere but Meethotamulla following the deaths and devastation on April 12, the Government is stirring up more anger across the city.

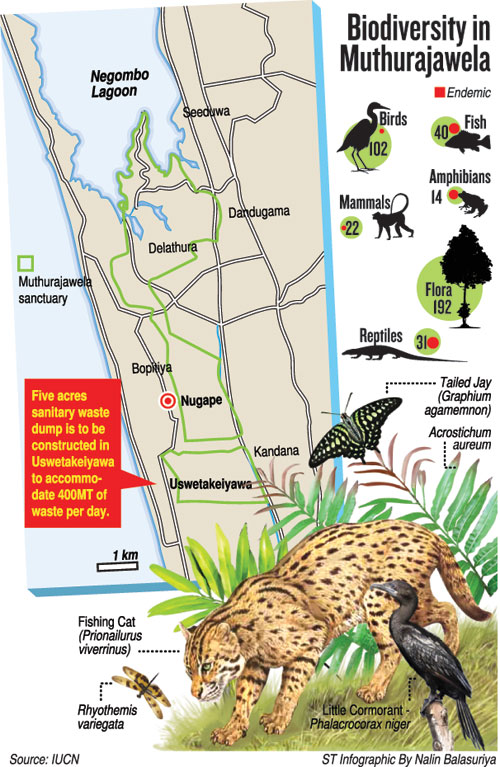

Residents of Bopitiya are up in arms over the garbage being dumped in Muthurajawela, a part of a wildlife sanctuary.

Residents and environmentalists say the area has been contaminated after several days of garbage dumping by the Colombo Municipal Council.

The Director General, Department of Wildlife Conservation, W. S. K. Pathiratna said yesterday, the dumping had begun while he was out of the country.

Residents complain that the garbage was dumped after a person had claimed ownership of the site.

They said they built their homes bordering the buffer zone of the Muthurajawela sanctuary and had requested approval from the Department of Wildlife Conservation, Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation, and the Agrarian Services.

They say approval had not been sought from the Central Environmental Authority before hauling solid waste to Bopitiya.

During a visit, the Sunday Times saw how people had blocked the narrow entrance to the lane of a housing scheme leading to the dumping site. Police were present.

Within the land, backhoes were seen excavating sand, while a part of the site was being used to dump garbage.

Rev Father Dinush Gayan, assistant parish priest of Bopitiya Church told the Sunday Times that about 300 tonnes of non-biodegradable waste are dumped in a single day.

He said that even when the Agrarian Services requested documents as well as environmental impact assessments, neither the owner of the site nor the government officials could provide them.

Rev Gayan said goons associated with the site owner disrupted a silent protest.

K.L Newton Perera, a lawyer who is also a resident of Nugape, Muthurajawela said some people are using the garbage to fill the land.

Mr Perera said the Meethotamulla dump also was created on marshy land.

“Bopitiya too is included to the Muthurajawela sanctuary and the dump site is also in a watery, marshy soil which stays wet during the dry seasons,’’ he said.

Anil Lankapura Jayamaha, the president of the Organisation for protecting the Muthurajawela Sanctuary, said that the government was dumping garbage by relying on the ownership claims of a person.

“The muddy soil and the waterways which people use for bathing, drinking and fishing, will be poisoned and cause health issues,’’ he said.

He said criminal gangs have moved in to extort money from garbage lorries, just as it was in Meethotamulla.

An official of the Agrarian Services, said 40 foot craters have been dug to dump waste.

The officer said she and officials wrote to President Maithripala Sirisena and the Colombo Municipal Commissioner, and were planning to go to court.

Meanwhile, Land Reclamation chairman, Asela Iddawella, said the Megapolis Ministry and local government offices of Wattala have proposed a waste dump.

The cabinet this week approved a recommendation for a site to manage 400 metric tonnes of waste per day on a five-acre site in the Muthurajawela area under the Wattala Divisional Secretary.

Mr Iddawela explained that the land at Muturajawela will be used to create an electric power plant, while another land will be used as a sanitary disposal site.

“The plant will create power from 500 tonnes [of waste] per day while a business model garbage dump will also be erected,’’ he said.

He said the waste-to-electricity plant will be operational after three years or a minimum of two years, while the sanitary land fill will take over 18 months.

He said the President also had asked that the engineering assessment and environmental impact assessment be done while the project continues.

The Director General of the Central Environmental Authority, K.H Muthukudarachchi said that the Megapolis and Western Development Ministry was carrying out garbage management programmes.

He said the CEA had done environmental impact assessments for two projects at Muthurajawela, undertaken by the Ministry of Megapolis and local councils.

He said garbage from Colombo will be dumped at Muthurajawela, Karadiyana and Aruwakkalu.

Environmentalist of the Biodiversity Conservation and Research Circle, Supun Lahiru Prakash, said that sanitary fillings are done after recycling various materials and by burying the most toxic waste.

He said the garbage will contaminate the waterways which support the bio diversity of the sanctuary.

He claimed that the private land in Bopitiya is within the vicinity of the sanctuary and the dump has caused damage already. He also warns of the flooding threat.

Mr Prakash said that the government move tramples on laws including wildlife legislation and also disregards a court order.

Source – 30/04/2017. The Sunday Times, See more at – http://www.sundaytimes.lk/170430/news/bopitiya-dump-stirs-up-garbage-danger-anger-238777.html