Sri Lanka Navy arrests 6 local fishermen illegally harvesting sea cucumber

May 08, Colombo: The Sri Lanka Navy Monday said it has arrested six local fishermen for allegedly engaged in illegal harvesting of sea cucumbers.

Naval personnel attached to the Northern Naval Area arrested the six persons while harvesting sea cucumbers using illegal fishing methods in the seas off Point Pedro yesterday (7).

Along with the suspects, approximately 280 sea cucumbers, 6 diving masks, 5 pairs of diving fins, 5 regulators, 4 diving torches, 20 oxygen bottles and 2 FGDs were also taken into naval custody.

The arrested persons and the items were handed over to the Fisheries Inspector, Point Pedro for onward legal action.

Sea cucumber fishing is not banned in Sri Lanka but allowed only with a permit to prevent over exploitation of marine species and adversely affecting the marine eco system.

Source – http://www.colombopage.com/archive_17A/May08_1494226096CH.php

World’s biggest star tortoise found in Lunugamvehera?

A star tortoise weighing 13 kilogrammes – believed to be the world’s biggest and heaviest – has been found by wildlife officers from the Lunugamvehera National Park.

This tortoise is believed to be the biggest tortoise found on far in the world. This tortoise which belongs to the Chelonian species has been recognized by the people as striped tortoise, forest tortoise,’ Mevara’ tortoise,’ Huniyan’ tortoise (Black magic tortoise), spring bean tortoise and Batakeya tortoise.

This species has got used and adapted to the dry land properly. The world’s biggest tortoise known so far is said to be weighing between 8 to 9 kgs. Therefore, wildlife officers are of the opinion that this is now the biggest tortoise that has been found in the world.

(Nayanajeewa Bandara)

Source – 09/05/2017, Dailymirror- See more at: http://www.dailymirror.lk/article/World-s-biggest-star-tortoise-found-in-Lunugamvehera–128586.html#sthash.0rowQtXr.dpuf

Galle’s wonderland that is ‘Serengeti’ By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

Sitting atop Galgamu-kanda, accessed by a winding, steep pathway is ‘Serengeti’ in Walahanduwa, with a view of the sea off Galle in the hazy and sunny distance.

‘Serengeti’ surrounded by lush greenery, large trees giving a wide canopy, smaller trees, plants, bushes and undergrowth is the home of Sarath and Premila Seneviratne.

Nay, it is not just the home of this retired couple, but also of bees, butterflies, birds and various small mammals.

It is a veritable birds’ paradise as we sit on the verandah sipping a delicious home-made drink from fruit picked from the garden with kasa-kasa temptingly at the top before a sumptuous luncheon, with a spread of vegetables also from the garden.

Suddenly, we hear the hungry chirping of baby birds and Sarath, with finger to lips, gently moves the branches of a kiri nuga bush near my chair to reveal a nest of the Red-vented bulbul with two nestlings in it.

A retired banker who has worked in remote areas, Sarath developed a passion for nature when his mother gifted him his very first book on birds when he was about seven years old and studying at St. Aloysius College, Galle. Their family home was at Hikkaduwa and he would keep cotton for birds such as bulbuls to take and make their nests. He would use the wall of his home as a marking-board to detail when eggs nestled within and when they would bring forth the babies. Later, as the family grew, he would keep a small bench to gain height to see the parent-birds feeding their young.

Being from a family of nine, Sarath who was the fifth boy says that there was no money for lavish spending and it was the pocket money for tiffin that he saved, when living with his Punchi Amma as it was closer to school. He would also ramble up the ramparts in search of birds, while scanning the newspapers to check out any books that were being published. Then he would make a beeline to the Universal Book Store in Galle to order them.

These precious acquisitions and much more including valuable collector’s items in the form of First Editions (all books of W.W.A. Phillips, G.M. Henry etc) tightly-line a large cupboard in his home. Details about the authors, including yellowed and frayed news-clippings and any letters Sarath had written to them along with the replies have been tenderly pasted on the books. This is while numerous photographs of birds are up on the walls.

The ‘wild’ trait had seen rapid progression, with Sarath joining the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society (WNPS) way back in 1961 as a schoolboy, being one of its oldest members recognized in 2012 as having an unbroken membership of 50 long years. Soon a request from well-known conservationist Thilo Hoffman — who has been credited with being the saviour of Sinharaja against its rape – had followed to join the Bird Club which he did most willingly in 1975.

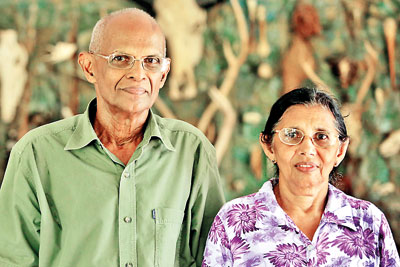

Nature lovers: Sarath and Premila

Sarath had also palled up with well-known author T.S.U de Zilwa and in an era when digital photography was still unheard of, to enable the ‘capture’ of bird-images in their different forms of nesting, feeding et al, would provide photography hides for him. (Such ‘hides’ are purpose-made constructions for a photographer to get closer to a bird than would be normally possible if he was in full view.)

“We would take-off on such missions over the weekend, build high scaffoldings and use the ‘hides’,” laughs Sarath going down memory lane to Kumana, Bundala and other locations where birds were aplenty.

These numerous images so captured adorn T.S.U’s lovely books.

Before we go on a tour of the nature wonderland that is ‘Serengeti’, Premila, goes back to those early days. They had fallen in love with the land but there was no water or electricity. Their very first action in the early ’70s was to construct a small tank for rain-water harvesting and then sit and think how they would lug the building materials needed for their home up the hill.

It was Premila who moved into their partially-built home with their eldest son, 10-month-old Hemantha. Two more sons enriched their family, Sampath (who incidentally has taken up molecular ecology and evolution as a Research Scientist & Senior Lecturer in Zoology at the University of Colombo) born in 1977 and Leelanga in 1980.

Gradually, Sarath and Premila turned this patch of land into an exotic beauty-spot — like its namesake National Park in Tanzania — where if there is a slight delay, the birds in the wild clamour for their food and recognize their small car, a Viva Elite, as it climbs the last stretch home, giving them a guard-of-honour.

By 1984, Sarath was also very much a part of the team taking the bird census which he continued even in challenging times such as the youth insurrection of 1988-89. Husband and wife would take the essentials including the telescope tied to the motorcycle and a bare minimum of a bottle of water, while their three sons were in school, and follow the trail of birds, once even passing the body of someone who had been killed in the unrest.

As a gentle breeze moves the foliage this way and that and common mynahs, Rose-ringed parakeets, sunbirds, White-backed munias, Black-hooded orioles and even the rare Yellow-naped green woodpecker fly around, butterflies flit from bush-to-bush, squirrels scurry hither and thither and a thalagoya (iguana) seems to show the way, we walkabout untroubled by the afternoon heat.

From the verandah, our first stop is the ‘amphibian cave’, the hollow of a tree; then passing creepers, bushes, plants and trees such as veni-val, kiri-nuga, magul karanda, an-kenda, uguressa, delum, atteria, all kinds of lime trees, we come upon the ‘bat hollow’ set up for insect-eating bats, and jump over a stile to take a look at the ‘vegetable patch’ of wetakolu (ribbed gourd), maalu-miris (capsicum), wattakka (pumpkin), karawila (bitter-gourd), iringu (corn), rabu (radish), nivithi (spinach) lovingly tended by Premila and then tea-lands and more. The rainwater harvesting tank is still intact but bigger.

Both Sarath and Premila are justifiably proud of the exotic orchids including the Vesak orchid (Dendrobium maccarthiae) and Vanda tessellata they have nurtured.

It is after a long and relaxing afternoon watching myriads of birds at ‘Serengeti’ that we bid goodbye to Sarath and Premila, in total agreement with Sarath that watching birds is a “bavanawa” (meditation) in itself.

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

Source – 07/05/2017,The Sunday Times, see more at – http://www.sundaytimes.lk/170507/plus/galles-wonderland-that-is-serengeti-239064.html

Fading fortunes of the native Vesak flower

A species of orchid that blooms in May and commonly called Vesak mal is becoming rarer. Plant experts say habitat loss and over collection from the wild are causing its decline.

Scientifically known as dendrobium maccarthiae, it may have got its local name because it blooms in the month of Vesak.

It is a light violet-pink flower with a paler lip and a purple blotch in the centre. It is a larger variety of wild orchid. The flower is about 6 centimetres long and 7.5 cm across. The photos accompanying this article were captured by Bushana Kalhara from the Kukulugala forest patch in Ratnapura two years ago in late May. He says the flowers were on the canopy about six metres above ground.

A specialist on orchids, Dr Suranjan Fernando, says the flower grows in south western lowland forest patches in Ratnapura, Kegalle, Kalutara and Colombo districts. The core area of the distribution is northern and western parts of the Ratnapura and Kalutara districts. It is also found in the western parts of Kegalle, southern part of Colombo and northern part of Galle district.

“The reason that this orchid is not found in other parts of the lowland wet zone is still a mystery,” Dr Fernando says.

Like most of the other wild orchids, it is an epiphyte plant that grows harmlessly on tall trees getting moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, and sometimes from debris accumulating around it. The species usually grows in the upper parts of the tree trunks and large branches of mature trees.

It is a popular Sri Lankan flower and has been featured in stamps issued in 1950 and 1994. The orchid is also the provincial flower of Sabaragamuwa.

The former head of the Botanical Gardens, Dr Siril Wijesundara, reveals that there was a plan to use the Vesak orchid as a local alternative to the poppy to commemorate war heroes following the end of the war against Tamil terrorists in 2009.

It has caught the attention of collectors and exporters since the colonial days because it is endemic to Sri Lanka. Collecting the orchids from the wild for ornamental purposes led to its decline in the 1900s. This led to its listing as a protected species from 1937 with the inception of the Fauna and Flora Ordinance. Even the Forest Ordinance protects the Vesak orchid.

The former head of the Customs Biodiversity Unit, Samantha Gunasekara who is also an orchid lover says he once saw an ad on e-Bay that listed a plant for sale.

He was certain that it had been gathered from the wild.

Dr Fernando says field observations in the past 10 years have shown that the flower is in decline.

A number of other wild orchids are also threatened.

In Sri Lanka, orchidaceae is among the largest families in the country with 191 known species with 57 endemic species. Orchids grow in many habitat types in Sri Lanka, but highest number has been recorded in diverse ecosystems found in the wet zone.

According to the 2012 National Red List of Threatened Fauna and Flora, four orchid species are likely to be ‘possibly extinct’ as they have not been recorded for a considerable time. Sixteen species are ‘critically endangered’, threatened with becoming extinct, while 54 species are categorised as ‘endangered’. And 60 species fall into the ‘vulnerable’ category.

A number of showy orchids are also in demand. The Red List 2012 lists phaius wallichii (star orchid), rhynchostylis retusa (fox tail), and vanda tessellata are commonly collected by growers and flower enthusiasts. Habenaria crinifera (naarilatha), ipsea speciosa (nagamaru ala), anoectochilus spp. (wanaraja), zeuxine spp. (iruraja), are taken from the wild for medicinal purposes and because of various mythological beliefs associated with each species.

Source – 087/05/2017/ The Sunday Times, See more at – http://www.sundaytimes.lk/170507/news/fading-fortunes-of-the-native-vesak-flower-239451.html

Declining loris populations risk lives on power lines

The rescued loris. Pic by Tharindi Pathirana An electrocuted loris. Pic by Chaminda Jayasekara

As tall trees in urban gardens become rarer, the loris appears to find electric wires an alternative way to move around. But many end up being electrocuted.

One lucky loris that got stuck on a power utility post last Monday was rescued in Anuradhapura town.

Young Tharindi Pathirana who lives near the SOS Children’s Village in Anuradhapura town heard screams around 9:00 pm. It lasted about 20 minutes. With her father’s help she began looking around and they found the frightened creature. But, by the time they reached the location, it had fallen to the ground. They took it home and alerted the wildlife officers, but they could not come until the following day to take custody of the animal.

Sri Lanka is home to two species of loris, namely, the gray slender loris and the red slender loris. These species have two subspecies, each restricted to various parts of Sri Lanka.

The Sunday Times contacted Chaminda Jayasekara – the naturalist of Vil Uyana hotel who also published a book about the loris to help identify the species that was saved in Anuradhapura. He identified the animal as a grey slender loris, which belongs to a subspecies scientifically categorized as loris lydekkerianus nordicus.

“I have come across at least five loris deaths due to electrocutions during the past six months. Last March, I saw a loris death at Kaduruwela in Polonnaruwa,” Mr Jayasekara says. He lists Polonnaruwa, Girithale, Anuradapura, Mihinthale as areas in which electrocutions occur often.

A number of loris have been seen in urban settings where power lines are abundant and it seems these insect hunters use the utility posts and lamp posts as places to find prey.

Mr Jayasekara also said he had witnessed a number of loris killed in collissons with vehicles on roads.

Loris researcher Saman Gamage says translocating these animals should be done with caution as there are a number of subspecies in various parts of the country. Translocating could result in species mixing.

Mr Gamage points out that loris populations can survive in many isolated patches of forest, but the numbers are declining.

By Malaka Rodrigo

Source – 07/05/2017, The Sunday Times – http://www.sundaytimes.lk/170507/news/declining-loris-populations-risk-lives-on-power-lines-239405.html

Hambantota elephants face bleak future

In a sad example of the plight of elephants in the Hambantota district, yet another animal alleged to have damaged properties and crops of residents in Kuda Indiwewa, Suriyawewa and Hambantota, was captured yesterday (4) and taken to Horowpathana elephant holding center.

The elephant was the 20th to be captured from the district and taken to the holding center.

Environmentalists say the holding center, which is spread across 2900 acres, lacks the necessary space and food needed for the elephants. Moreover, since only large and strong male elephants are held at the center, it removes elephants with good genes from the wild, which has a negative impact on the elephant gene pool.

They also claim that male elephants newly taken to the holding center risk being attacked by other males. There have even been reports of some elephants being badly injured in these attacks. The reason for the attacks is that the holding center does not have enough female elephants to meet the reproductive needs of the males.

Wildlife officers said the elephant captured yesterday was a large male about nine feet tall and about 35 years old.

Area residents say about 15 houses in the Suriyawewa area alone have been damaged during the last three weeks due to elephant attacks.

Officers from the Department of Wildlife Conservation’s (DWC) Hambantota office said they had no option but to capture the elephant as area residents were demanding it as the animal was damaging their properties.

According to the DWC, the number of wild elephants in the Hambantota district have increased from about 350 to 400 during the last 10 years. However, while elephant numbers have increased, their habitat has gradually shrunk, leading to more human-elephant conflict.

Available data reveals 25 persons in the Hambantota district have been killed from 2010 to 2017 due to elephant attacks. The number of properties damaged by elephants during the same period is 347. Meanwhile, 58 elephants have been killed at the hands of humans.

Story and Pix by Rahul Samantha Hettiarachchi

Source – Times Online, See more at –

Largest star tortoise in Sri Lanka found from Lunugamvehera

The largest star tortoise ever recorded in Sri Lanka has been found from the Lunugamvehera National Park. The tortoise is 45cm in carapace length (carapace is the hard upper shell) with a shell height of 22cm and a Paltron length of 42cm. It weighs 13.93kg.

There is speculation that the tortoise may even be the largest star tortoise in the world.

Wildlife Veterinarian at the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC), Dr. Vijitha Perera is currently examining the tortoise to verify whether this is indeed the case.

By Rahul Samantha Hettiarachchi

Source Times Online, 06/05/2017See more at – http://www.sundaytimes.lk/article/1021401/largest-star-tortoise-in-sri-lanka-found-from-lunugamvehera

Concerns over Cabinet paper ordering release of detained elephants

The government’s decision to handover the elephants involved in court cases back to their owners for a bond of Rs.10 million with a valid license was not merely a violation of the law, but also an encouragement to all those who illegally possess elephants, Environmentalist Jagath Gunawardena said recently. “Sustainable Development and Wildlife Minister Gamini Jayawickrema has submitted a Cabinet paper ordering the release of 35 detained elephants with the intention of using them for religious events. However, if there were a shortage of tamed elephants for this purpose, then the relevant authorities could hire such elephants from the tourism industry. There is no need to release detained elephants to fill the void by violating several laws including the Flora and Fauna Act,” Mr. Gunawardena told a news conference recently. Attached with the Cabinet paper is a report, devised by a special committee headed by Minister Sarath Amunugama, which recommends the confiscation of five elephants from the owners who did not hold a valid license. “There are six cases in courts in connection with the registration of elephants. In many cases, the poor animals die while in captivity. It is however recommended that legal action be taken against those who aid and abet to produce forged documents to acquire the elephants. Most of the accused are wildlife officers,” Mr. Gunawardena said.

The government’s decision to handover the elephants involved in court cases back to their owners for a bond of Rs.10 million with a valid license was not merely a violation of the law, but also an encouragement to all those who illegally possess elephants, Environmentalist Jagath Gunawardena said recently. “Sustainable Development and Wildlife Minister Gamini Jayawickrema has submitted a Cabinet paper ordering the release of 35 detained elephants with the intention of using them for religious events. However, if there were a shortage of tamed elephants for this purpose, then the relevant authorities could hire such elephants from the tourism industry. There is no need to release detained elephants to fill the void by violating several laws including the Flora and Fauna Act,” Mr. Gunawardena told a news conference recently. Attached with the Cabinet paper is a report, devised by a special committee headed by Minister Sarath Amunugama, which recommends the confiscation of five elephants from the owners who did not hold a valid license. “There are six cases in courts in connection with the registration of elephants. In many cases, the poor animals die while in captivity. It is however recommended that legal action be taken against those who aid and abet to produce forged documents to acquire the elephants. Most of the accused are wildlife officers,” Mr. Gunawardena said.

http://www.dailymirror.lk/article/Concerns-over-Cabinet-paper-ordering-release-of-detained-elephants-128323.html#sthash.S6a6byC9.dpuf

New homes for Sri Lankan tuskers

The decision last week overturning a ban on elephant adoption came as a surprise

You don’t have a Sri Lanka souvenir until you have one sporting an elephant. The Asian tusker has made it to nearly all memorabilia — from t-shirts to tea packets and stationery. Traders possibly believe that you can’t sell a souvenir without the elephant validating its ‘Sri Lankan-ness’.

My first encounter with a Sri Lankan elephant was four summers ago at an elephant orphanage — one that had 88 of them — in Pinnawala, some 100 km northeast of Colombo. I went up a raised wooden platform to feed a piece of watermelon to one of them. The elevation was to help us look the beast in the eye. The orphanage-cum-captive breeding centre fascinated me, with its milieu consisting of a big herd of elephants, once abandoned, now living in a shared open space, the centre supported by the tourism it spawned.

Some time later, my friends pointed to baby elephants being chained there, instantly guilt-tripping me. I felt bad but only till I saw the elephants again. The sight of so many elephants — their back shining after a long bath — parading on a narrow lane was captivating. I have been there thrice since, the charm remaining alive.

Last week, the country suddenly overturned an earlier ban on adopting baby elephants. It was a response to “overcrowding” at Pinnawala and the consequent pressure on resources, the government said. Elephants in the orphanage are now available to individuals or institutions for adoption. The move came as a surprise, especially at a time when President Maithripala Sirisena has signed a major gazette notification on wildlife conservation.

While temples will get them for free, individuals will have to pay about $66,000 for each tusker. Elephants were a part of temple traditions and processions since the time of the ancient Kandyan kingdom, and the decision is in line with that, explained a senior Minister, adding that “even if the elephants are given away, we will monitor them”.

I don’t know if an elephant will get a better home, but what if the move ends up separating some elephants from their families?

Source – 03/04/2017, The Hindhu, see more at – http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-opinion/new-homes-for-sri-lankan-tuskers/article18365676.ece

700 to 1,000 leopards in Sri Lanka; researcher

There are about 1,000 leopards across Sri Lanka and they are a keystone species in ecological parlance of the country, a wildlife researcher has said.

An article published on the website of multimedia publication ‘Motherboard’ under the title ‘Saving Leopards Is Hard, Especially with All the Landmines’ by Smriti Daniel, said leopards are more important to the ecosystem than their numbers would suggest.

Wildlife researcher Anjali Watson has said that leopards are an “umbrella species” – because they are wide-ranging animals, protecting them would mean protecting many others in the same territories.

Wilpattu, Sri Lanka’s oldest and largest national park, was once a warzone. The fighting between the Sri Lankan state and the militant separatist group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) that began in the 1980s had spilled over into these wild lands.

Wildlife researchers Anjali Watson and Andrew Kittle remember hearing stories from soldiers stationed in these forests. The men recalled nights when they would be jolted awake by the sound of landmines exploding in the pitch darkness, somewhere beyond the border of their camps. Nervously, they wondered whether guerillas had triggered the bombs, and if their enemies would soon close in on them.

But the dawn would bring evidence of a different kind of victim. The remains of peacocks were found lying in heaps of shredded feathers; elephants lay with limbs blown off. “A few leopards and bears were also shot because men who encountered them were afraid,” Watson told me, explaining that the thick, thorny forests often swallowed any evidence.

The park itself was off limits to the researchers during the conflict. But even after a ceasefire signed in 2002, it remained unsafe—a mine claimed the lives of a jeep full of wildlife enthusiasts in 2006 and a year later, Wilpattu’s park warden Wasantha Pushpananda was ambushed and killed by the LTTE while on an inspection tour with his team.

It wasn’t until the nearly 30-year-long war came to an end in 2009, and many landmines laboriously cleared, that Watson and Kittle were able to readily move about Wilpattu again. They are now publishing data from one of the most comprehensive studies of the leopard population in Wilpattu—the first since the Smithsonian Institution did a more general survey in the late 1960s.

A husband and wife team, Kittle and Watson head The Leopard Project at the Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Trust (WWCT) in Sri Lanka. They have been studying leopards for over a decade and were responsible for gathering the data that put the native big cat on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of endangered species in 2008.

“Being on the Red List influences both conservation and funding attention,” Watson said, explaining that IUCN tracks the global status of various species. In Sri Lanka, the state’s conservation programs had previously been focused overwhelmingly on the elephant, but the IUCN listing has driven a surge of interest in the leopard and its significance as an apex predator—residing comfortably at the very top of the food chain on this island.

Kittle, Watson and I meet in their small office, perched above a garage in central Colombo, the commercial capital of Sri Lanka. The two sit across from each other and share a desk, seeming to be seldom out of each other’s company. Their rhythm has roots—the two met in university and have since travelled widely, always working closely together as a team. When their children were born, they simply took the kids along to the field, something they continue to do. Little drawings by Ayla and Amara decorate an entire wall in their office.

Watson said she and Kittle first knew they could make such a close partnership work when they were assigned to help reestablish a wild population of native primate species on an uninhabited island on the Panama Canal in the late 90s.

“There was just the two of us, and a guard who spoke Spanish,” Watson tells me, laughing. “I spoke no Spanish, Andrew spoke some Spanish, and the only other contact we had was a boat coming in every Saturday to bring us provisions. We spent nearly two years there, and I thought if we could do this…”

Today, though their work still might take them far afield, Sri Lanka is home—Watson said her heart is with this island because she grew up here. The duo are working toward establishing a comprehensive habitat use plan for the Sri Lankan leopard by 2020, including a population distribution map, and assessments of its habitats across the island. But tracking this predator has always presented a challenge.

When Watson and Kittle first told me this, I was surprised. I have seen leopards in Yala National Park in southeast Sri Lanka, where the big cats draped themselves decoratively over high branches and rolled around on dusty trails as tourists watched. But Kittle explains that in Wilpattu, and pretty much everywhere else in the island nation,the Panthera pardus kotiya is notoriously shy.

“Usually cryptic carnivores like this are really difficult to spot,” he said, adding that leopards manage to remain elusive despite existing in relatively high numbers in little pockets across the island.

Now, in the Peak Wilderness Sanctuary in central Sri Lanka, where tea plantations abut dense forest, encounters between leopards and people are on the rise. As more and more wilderness is cleared, Kittle and Watson say leopards and other animals are increasingly moving around and even breeding in ‘habitat mosaics’, or heavily fragmented forested areas surrounded by a patchwork of farms, plantations and homesteads. As a result, villagers are reporting more leopards sightings.

With one legendary exception—in the 1920s, the ‘maneater of Punanai’ was a voracious killer—Sri Lankan leopards are not maneaters.

In Dickoya, people have escaped encounters with the animal with just some deep scratches. Watson and Kittle, increasingly called on to reassure nervous communities, use these incidents to help convince villagers that the leopards are likely as frightened of the people as the people are of them. Working closely with the management of sprawling tea estates, they are now trying to find ways to prevent humans from barging in on the leopards. But to do this, they first have to know where they will be.

In the years that Watson and Kittle have been out in the field, they’ve seen the tracking technology available evolve. In their earliest forays into the field, they would rely on sighting the animals directly and recording each encounter. Some of Yala’s leopards, such as one who boasted bold spots in the shape of a ‘W’ on his forehead, were immediately recognizable, others could only be identified by closely examining photographs of the unique pattern of rosettes on their bodies.

The couple would also rely on tracing Paw Impression Pads: sweeping leaf litter away from a likely spot, they would create a sandy clearing, then return to record pugmarks. This technique allowed them to set up TrailMasters, camera traps that ran on film, to monitor spots where there was a lot of leopard traffic.

Watson and Kittle stuck with the technology up until 2012, before they switched to digital cameras. Film cameras could be cumbersome in the field, demanding hooking up wires and multiple components, but digital ones offered better battery life, were usually more weather resistant, and enabled them to get results faster and cover larger areas.

Ironically, conservationists must often rely on technology developed for hunters, Kittle said, but at least there are hundreds of cameras to choose from. Currently, they use Scoutguard SG565F cameras which have an incandescent flash (old style, bright white). “This is not de rigueur these days in remote camera work as infra-red or low-light flash is the thing,” Kittle said.“But we need to identify individuals in order to estimate population densities etc. and only incandescent flash is capable of that for a moving animal.”

However, the technology still comes with its own share of glitches. “The camera trap is triggered by data from a highly sensitive Passive Infra-Red motion sensor,” said Watson, adding that deploying this technology in Sri Lankan parks has been a steep learning curve. “In Wilpattu we found that the sun rays in the morning could interfere with the beam, and we would have 3000 shots of sunlight,” she said.

“In the Horton Plains dew and mist would trigger the trap, in Ritigala ants were building nests inside the lens, and in the Peak Wilderness Sanctuary we have all these pictures of leopards with a spider web across one corner of the image. Thank god, they were still usable.

” Watson says that there are between 700 and 1000 of this apex predator across the 65,000 sq km island. “They are a keystone species, in ecological parlance,” Watson told me,“They are more important to the system than their numbers would suggest.” She explained that leopards are an “umbrella species” – because they are wide ranging animals, protecting them would mean protecting many others in the same territories.

The team uses scat—i.e. leopard feces—analysis to understand the leopards’ diet and hunting patterns. “Felids have very short guts and pass out hair, bones, nails, quills etc. undigested,” said Kittle. Efforts are underway to fine tune mathematical equations that can then transform scat analysis output into an estimate of biomass consumed, providing a clearer, more reliable picture of leopards’ dietary choices.

Kittle and Watson have watched the post-war transition with interest, and have been curious about the conflict’s impact on local wildlife. Watson points out that war can lead to decimation of habitats and rampant poaching, but that in other cases “mines can also keep people out”, somewhat protecting wildlife from human intervention or development.

Now, as people return to the formerly war torn areas in the north and east, they have begun reclaiming lands or clearing new acres in previously untouched areas like the sprawling forests of the Wanni. They’re building homes and preparing the once wild land for farming. But this trend is not confined to one part of the island, and everywhere protected areas are coming under threat.

“I think the big concern is the pace of this whole post-war development drive,” warns Watson. “There is so much we don’t know, so many areas we haven’t explored. We could be losing species we never even knew about.

But Kittle said studying the leopard has left him “tentatively optimistic.” “For us, there’s always this thrill, no matter how often you see the animal. You have this respect for its ability to exist in very compromised locations, often alongside people, with minimum conflict. You have to admire that.” –

http://www.dailymirror.lk/article/-to-leopards-in-Sri-Lanka-researcher-121683.html#sthash.sRtrpbKf.dpuf